[ENG-SPA] From Stigler's law to the Q source (things I learnt this week) | De la ley de Stigler a la Fuente Q (cosas que aprendí esta semana)

I discovered Stigler's Law through an interesting Scientific American article that shows that 8000 people in the world have the same amount of hair on their heads using the pigeon hole principle (if a certain amount of pigeons are distributed in a smaller amount of pigeon holes, then there will necessarily be some pigeon hole that has more than one pigeon).

The general idea of this law is well known, but, like so many other things, I did not know it had a name. What it comes to enunciate is that no scientific discovery is named after the person who discovered it. We have all surely read one of those stories of discoveries where it is not at all clear who came up with the idea first, and it always turns up someone not very well known who had already formulated the same idea before. Of course, Stigler's law applies to itself. Stephen Stigler himself, who enunciated the law in 1980, admitted that the principle in question had already been enunciated by Robert K. Merton.

There are lots of known examples of this law. Perhaps the most extreme is the famous Snell's Law (i.e., the law of refraction), enunciated by Willebrord Snel van Royen (Snellium to his friends) in the 17th century. It turns out that it had already been formulated ten centuries earlier! by the Persian mathematician Ibn Sahl, who took up Ptolemy's work and was a precursor of the great Arab physicist and astronomer Alhazen.

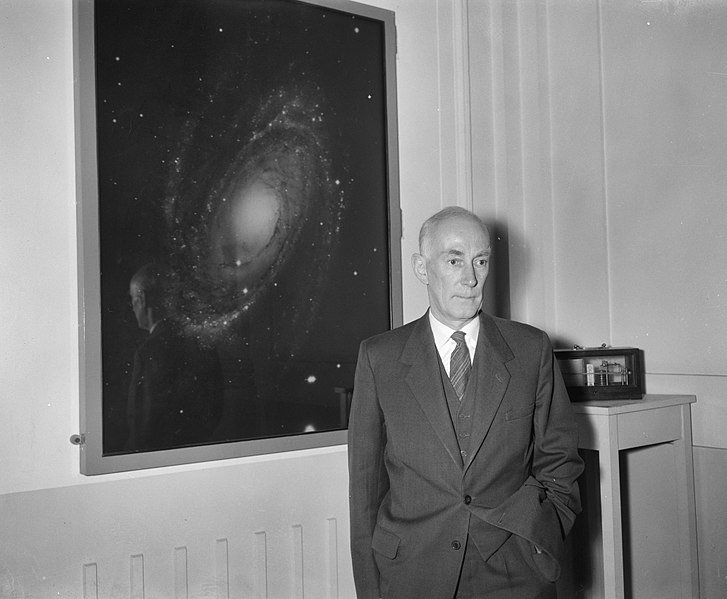

Willebrord Snel van Royen. Source

Among the many examples I found of Stigler's law, I was also struck by that of the Oort cloud (that cloud of trans-Neptunian objects that is almost a light year away from the Sun), named after the Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, but which had been proposed some 20 years earlier by an Estonian astronomer, Ernst Öpik.

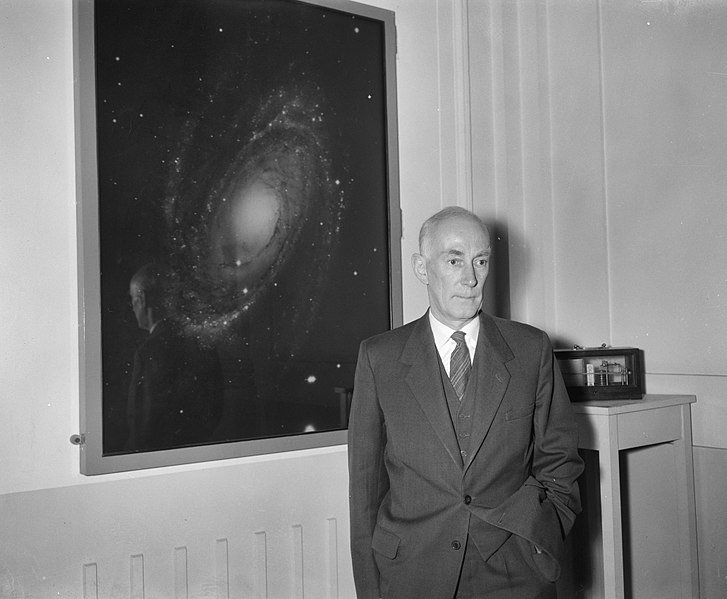

Jan Oort. Source

Why does it happen so often that scientific discoveries are attributed to people other than the "true" discoverers? One possible explanation is found in the Matthew effect, apparently first enunciated by Robert K. Merton, whom I mentioned a few paragraphs ago. It is based on the parable of the talents in the Gospel of Matthew, where it is said that "for to every one who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away", i.e., the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. In the same way, those scientists or writers who have greater prestige will receive greater recognition, which will give them greater prestige... Thus, when a little-known scientist makes a discovery, it is likely that it will be forgotten and will not receive any recognition until some scientist with greater prestige takes up the idea. This does not mean that it is theft, far from it. Stigler, for example, acknowledges that his idea had already been enunciated; Snellium has probably never read Ibn Sahl, and Oort apparently arrived at his results independently of Öpik. What matters is that the name and recognition goes to the one who already has prestige.

The Matthew effect has many applications. It happens all the time in everyday life. And also in Hive, of course, because after all our blockchain is part of the world. Authors with higher reputations get higher votes, and authors with lower reputations get almost no votes, even if their posts are great. You can also see this effect when some web 3 games give out a daily pool to those at the top of the leaderboard. Those who are at the top of the leaderboard and get the rewards are the ones who invested the most money (probably the richest ones). That mechanic, then, only increases the inequality between rich and poor. I would love, sometime, to see a game that would try to decrease that gap instead of increasing it.

But back to Stigler's law. The Matthew effect is so called because, somehow, it seems to have been enunciated in the first place by Matthew. But, if we apply Stigler's law? The fact is that there is a very similar parable in Luke's Gospel, the parable of the minas. The two Gospels were written around the same time. These similarities between the two texts (and between many other parts of these gospels) led some scholars to suppose that they both start from a common source, a lost collection of sayings of Jesus which they called Q Source or Q Gospel. It is only a hypothesis, but also a nice closure to this story.

Descubrí la Ley de Stigler a través de un interesante artículo de Scientific American que demuestra que 8000 personas en el mundo tienen la misma cantidad de pelos en la cabeza usando el principio del palomar (si una cierta cantidad de palomas se distribuyen en una cantidad menor de palomares, entonces forzosamente habrá algún palomar que tenga más de una paloma).

La idea general de esta ley es bien conocida, pero, como tantas otras cosas, no sabía que tenía un nombre. Lo que viene a enunciar es que ningún descubrimiento científico lleva el nombre de quien lo descubrió. Todos hemos leído, seguramente, alguna de esas historias de descubrimientos en los que no está nada claro a quién se le ocurrió primero y siempre aparece alguien no muy conocido que ya había formulado antes la misma idea. Por supuesto, la ley de Stigler se aplica a sí misma. El mismo Stephen Stigler, que enunció la ley en 1980, admitía que el principio en cuestión ya había sido enunciado por Robert K. Merton.

Hay montones de ejemplos conocidos de esta ley. Quizás el más extremo sea la famosa Ley de Snell (es decir, la ley de refracción), enunciada por Willebrord Snel van Royen (Snellium para los amigos) en el siglo XVII. Resulta que ya había sido formulada ¡diez siglos antes! por el matemático persa Ibn Sahl, que retomó la obra de Ptolomeo y que fue un precursor del gran físico y astrónomo árabe Alhazen.

Willebrord Snel van Royen. Fuente

Entre los numerosos ejemplos que encontré de la ley de Stigler, me llamó la atención también el de la nube de Oort (esa nube de objetos transneptunianos que está a casi un año luz del Sol), que debe su nombre al astrónomo neerlandés Jan Oort, pero que había sido propuesta unos 20 años antes por un astrónomo estonio, Ernst Öpik.

Jan Oort. Fuente

¿Por qué ocurre con tanta frecuencia esto de que los descubrimientos científicos se atribuyen a personas diferentes a los "verdaderos" descubridores? Una posible explicación se encuentra en el efecto Mateo, que aparentemente enunció por primera vez Robert K. Merton, a quien ya mencioné unos párrafos atrás. Se basa en la parábola de los talentos del Evangelio de Mateo, donde se dice que "a cualquiera que tiene, se le dará, y tendrá más; pero al que no tiene, aun lo que tiene le será quitado", es decir que los ricos se hacen más ricos y los pobres, más pobres. Del mismo modo, aquellos científicos o escritores que tienen mayor prestigio recibirán mayor reconocimiento, lo que les dará mayor prestigio... Así, cuando un científico poco conocido realiza un descubrimiento, es probable que este quede en el olvido y no obtenga ningún reconocimiento, hasta que algún científico con mayor prestigio retome la idea. Esto no quiere decir que se trate de un robo ni mucho menos. Stigler, por ejemplo, reconoce que su idea ya había sido enunciada; Snellium probablemente nunca haya leído a Ibn Sahl, y Oort al parecer llegó a sus resultados de manera independiente a Öpik. Lo que importa es que el nombre y el reconocimiento queda para el que ya tiene prestigio.

El efecto Mateo tiene muchas aplicaciones. Ocurre todo el tiempo en la vida diaria. Y también en Hive, claro, porque después de todo nuestra blockchain forma parte del mundo. Los autores que tienen mayor reputación obtienen mayores votos, y los que tienen menor reputación casi no son votados, aunque sus post sean geniales. También se puede ver este efecto cuando algunos juegos web 3 reparten un pozo diario entre los primeros en el leaderboard. Aquellos que están arriba en el leaderboard y se llevan las recompensas son los que invirtieron más plata (los más ricos, probablemente). Esa mecánica, entonces, solo aumenta la desigualdad entre ricos y pobres. Me encantaría, alguna vez, ver un juego que tratara de disminuir esa brecha en lugar de aumentarla.

Pero volvamos ahora a la ley de Stigler. El efecto Mateo se llama así porque, de algún modo, parece haber sido enunciado en primer lugar por Mateo. Pero, si aplicamos la ley de Stigler... El caso es que hay una parábola muy parecida en el Evangelio de Lucas, la parábola de las minas. Los dos evangelios fueron escritos más o menos en la misma época. Estas semejanzas entre los dos textos (y entre muchas otras partes de estos evangelios) hizo suponer a algunos estudiosos que ambos parten de una fuente en común, una colección perdida de dichos de Jesús a la que llamaron Fuente Q o Evangelio Q. Es solo una hipótesis, pero también un lindo cierre para esta historia.

Original in Spanish. Translated with Deepl.

Original en español. Traducido con Deepl.

Hey @agreste!

Actifit (@actifit) is Hive's flagship Move2Earn Project. We've been building on hive for almost 5 years now and have an active community of 7,000+ subscribers & 600+ active users.

We provide many services on top of hive, supportive to both hive and actifit vision. We've also partnered with many great projects and communities on hive.

We're looking for your vote to support actifit's growth and services on hive blockchain.

Click one of below links to view/vote on the proposal:

https://leofinance.io/threads/@agreste/re-leothreads-24epjqvyk

The rewards earned on this comment will go directly to the people ( agreste ) sharing the post on LeoThreads,LikeTu,dBuzz.

Son interesantes los puntos que señalas. No conocía la historia, pero recordé sobre el invento del teléfono y como este se disputa entre Alexander Graham Bell y Antonio Meucci en La Habana.

Fue sin duda una buena lectura.

¡Muchas gracias! Sí, la historia de Graham Bell y Meucci es oscura. Hay casos de robos, y otros en los que dos personas inventan lo mismo con poca diferencia de tiempo sin saber realmente lo que estaba haciendo el otro. El caso del teléfono parecería estar más cerca de la primera opción. ¡Saludos!

Yay! 🤗

Your content has been boosted with Ecency Points, by @agreste.

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more

You about had me at Snellium. I'm going to be thinking of that all day now.

One of my takeaways from this is that people have been stealing other peoples ideas for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. A more positive take is that we as a people continue to build upon the body of knowledge that came before us, with no one really "new" thought, but continued advances in ideas and knowledge that improve what we already know, or believe to know.

Thank you for sharing! This was fun to read.

Yes, science is not isolated from the world, so there is a little bit of everything, from theft to people who build honestly from the work of others. I don't know, but I'd like to think the latter are in the majority. Cheers!